Welcome to the banquet

As part of our Advent preparation here, we’ve been reading and watching C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe,” and there’s a banquet scene in it where the children are gathered at the beaver’s house for a great feast. One of the children, however—Edmund—abandons the banquet. He is unable to be fully present there because he is distracted—self-absorbed—possessed—by thoughts of the White Witch and the temptation of her Turkish Delight and her promises of prestige and power. Edmund slips out of the celebration, abandoning its offering of nourishment and family and love, escaping to what will eventually become his own, private, hell.

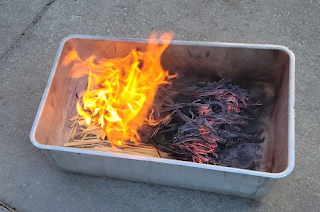

In one of his other books, The Great Divorce, C.S. Lewis explores this idea of us separating ourselves from the heavenly banquet as an apologetic for heaven vs. hell. Separation, to be forever cut off from God’s love and God’s presence, forever unable to know God’s love and God’s mercy, would be like being thrown into a burning lake of fire. Think of it this way: Salvation, offered to all freely, is like a party at a huge picnic table banquet: We can acknowledge the gift, enjoy the feast, participate in the joy—or, we can wither inside ourselves, becoming smaller and smaller, increasingly self-absorbed, until, like an ant, and then, having shrunk to atomic singularity, we become completely unable to even see the gifts around us—we fall through the table placed before us, unable to know that it is there, offered, in our midst and all around us, because it’s so huge and abundant, and we’re so small and self-focused.

Rabbi Rami Shapiro, in his book The Sacred Art of Lovingkindness, puts it this way: “God's compassion extends to all creatures....God's love is infinite and unbounded. It cannot be earned and it cannot be lost. But it can be ignored” (p 23). And I think the reason we ignore it is because we’re afraid: we’re afraid that acknowledging our sinful state and accepting God’s forgiveness and taking a seat at God’s banquet will force us to admit we’re not in charge, admit we can’t do it ourselves, admit we’re frail, dependent creatures, admit we’re not in control, admit we’re afraid…admit we can’t pay for it ourselves…admit we don’t really deserve it.

|

| http://radiantlight.org.uk |

They had much to fear, these people in the Christmas story: How can aged people at the end of their lives care for a new baby who is destined to be a prophet? (And aren’t prophets ignored and even killed by their people?) What will happen to the poor engaged young woman, when she is found to be pregnant? What will happen to the shepherds’ flocks, and their livelihood, if they abandon them for some wild story about a new king—and how stupid would you have to be to go looking for such a king in a stable? What will the Romans do to someone who is born claiming to be a king?

God sent out the invitation, set out the heavenly banquet, laid out the plan of salvation for all creation, in front of these people, and—even though it was impossible and terribly fearful—they gave themselves over to God and to God’s ancient promise—God’s promise made long ago to Abraham—God’s promise of mercy and compassion—God’s promise that the proud would be scattered in their conceit—God’s promise that the mighty would be cast down and the humble lifted up—God’s promise that the hungry would be filled and the rich sent away empty—God’s promise of mercy and compassion—God’s promise of salvation.

God invites us to give ourselves over to that promise today. How often do we say, like Mary, “this is impossible.” It’s not possible to love the unlovable. It’s not possible to respond to evil and hatred with anything other than retribution. It’s not possible to give generously until we have “extra.” It’s not possible to escape our past and build a more just world. It’s not possible to feed all the hungry children. It’s not possible to combat homelessness. It’s not possible to fight addictions. It’s not possible.

As we all wrap up our advent preparation today and enter into the season of Christmas later tonight, I invite us all to spend these last few hours in preparation. What fears of the impossible are preventing us from being truly present at the banquet God lays out in front of us—the banquet at this altar, and the banquets available to us in every hour of every day? What banquets are we running out of, like Edmund, in fear that we’ll be exposed for what we are—frail, poor, selfish, helpless sinners. What preparation can we do that will give us the humility and faith that Mary had, so that, when confronted by the impossible, we can say, like Mary did, “Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word.”

Greetings, favored ones, the Lord is with you…Fear not…For nothing will be impossible with God. Welcome to the banquet!

Comments

Post a Comment